I've Been Brainstorming About...How I Like Abstraction in Art, But Not in Writing

Give me a way to ground myself in your story

I’d be so grateful if you drop a heart on this newsletter, forward it to a friend, or share it on social media. Or subscribe to get me in your inbox! I love hearing from you, so you can hit reply and email me any time. And I adore comments!Writing these newsletters is part of how I make a living as a writer, so I welcome paid subscriptions, too.

The other evening the four-year-old came in1 while my husband and I were eating dinner: take-out from a Mexican place. Along with my Alambre I’d received a container of rice and beans. Tucker looked at my rice and beans.

“I like rice,” he said.

This is his cue for me to share my food.

Then he looked at my tortilla (flour, if you must know).

“I like those,” he said. (A bit speech-delayed, he doesn’t have the word for tortilla yet.)

I thought of Tucker as I started writing this newsletter.2

Because, “I like abstract art.”

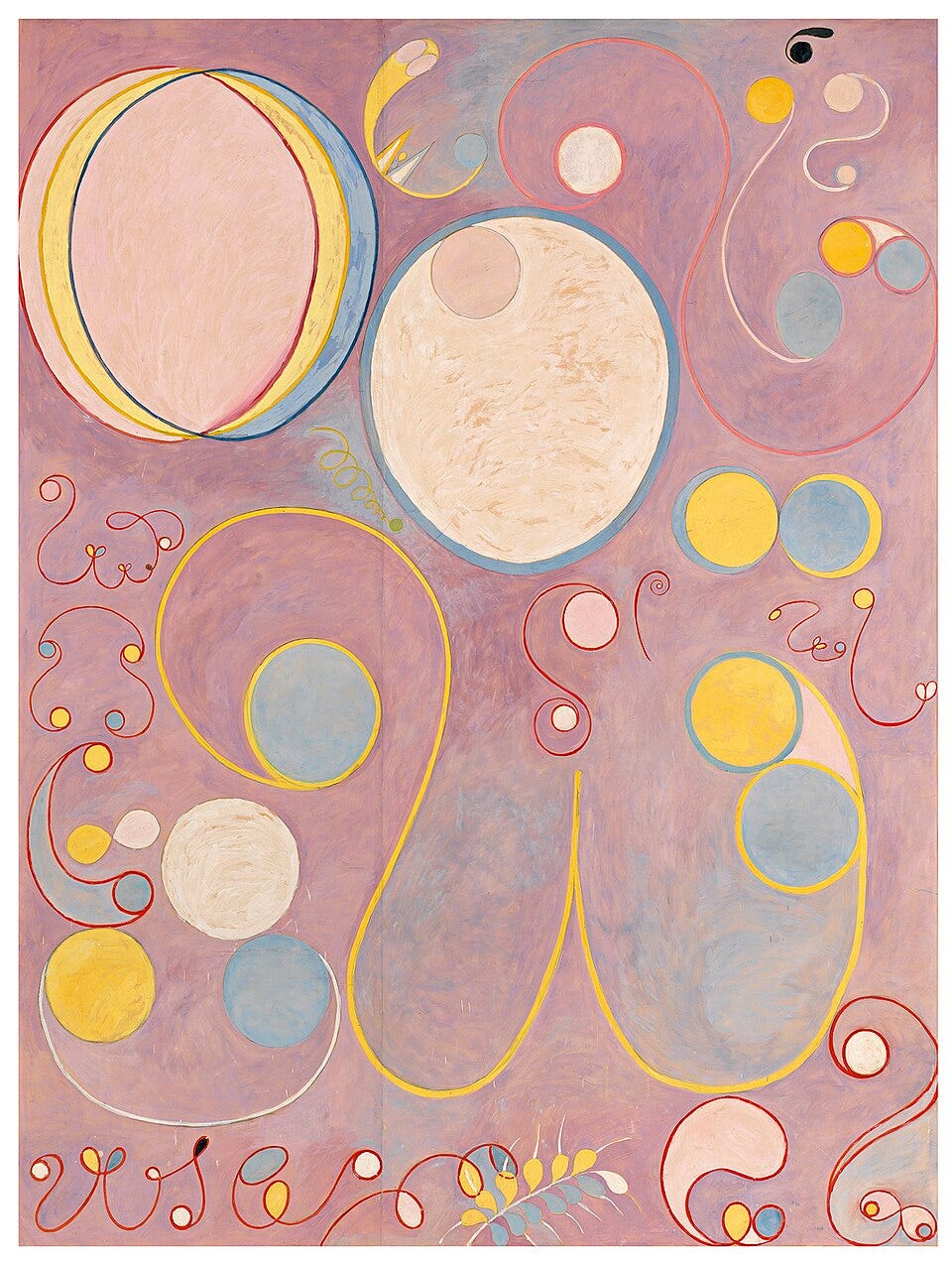

Like this:

Or this:

But what I don’t like is abstract writing, like this:

To be happy, spread love. Spread it all around and then you will feel better and you won’t be sad but happy and joyful.3

Or this:

Love is a powerful feeling that brings warmth to your heart and a smile to your face when you think about someone special. It's that mix of excitement and comfort you feel when you're with a person who matters deeply to you. Love makes you want to care for someone, to protect them, and to put their happiness alongside your own. It can make your heart race when they enter a room or give you a sense of peace just knowing they exist in your world. Love connects people in a unique way, creating bonds that can weather hard times and celebrate good ones. It's both the quiet contentment of belonging together and the passionate desire to be close. At its core, love is about accepting someone completely while wanting to grow together through life's journey.4

I wrote the first example and Claude AI wrote the second. Do either of these mean anything to you? No, no they do not. And here’s why: Claude and I used only vague concepts like love and happy and joyful and feel better. There’s nothing concrete there, no sensory details, no connections to people, places or things. In other words, nouns. Nouns are tangible. Nouns connect us to reality, to the thereness of placeness, the real feel of people.

Here is a definition of definition of abstract that I found on the internet: existing in thought or as an idea but not having a physical or concrete existence.

In case you haven’t guessed by now, in my world, abstract is 👎🏻 and concrete is 👍🏻.

I often read abstraction-heavy prose in non-fiction books, particularly the self-help realm. Pro tip: if you’re writing non-fiction, include stories. That’s how we humans related to otherwise abstract concepts.

Abstraction in Fiction

But we talk mostly about fiction here.

In fiction (and memoir) abstraction often comes about most often when a character is thinking, when a character is in action but we have no sense of where in the world she is, or when we have the dreaded talking heads. These are the ways I most often see clients go astray.

When a character is thinking

Nothing wrong with getting us into a character’s head. That’s what sets novels apart from screenplays or stage plays. In a novel, we get access to a character’s thoughts. In a piece of writing that needs to be actable, we do not. But I often notice in manuscripts that such thoughts are not tied to anything. All of a sudden, out of the blue, the protagonist will start thinking about something unrelated to what’s going on. Such as:

She watched the rain falling in huge plops onto the patio. Another cold, dreary winter day to drag herself through. She wondered where she’d left her ring.

There’s an easy fix for this. Tie the thought leap to something concrete. (Haha, you knew that was coming, right?) So, instead, we get:

She watched the rain falling in huge plops onto the patio. Another cold, dreary winter day to drag herself through. It had been a day like this when Kevin gave her the ring, and that was the only thing good about the rain. She wondered where she’d left that ring.

Instead of the random leap from rain to the ring, we see that there is a reason for it. Showing something concrete is a good way to do this if you’re transitioning into a flashback: She glanced at the ring on her finger and remembered the rainy day Kevin had given it to her. Boom! Proceed to flashback.

(Forgive me, I know these are silly examples, but I’m trying to be blatant here so you get what I’m saying.)

When a character is in action but where?

You can have everything going right in your scene, with action, dialogue, interiority. Except for one thing: we have no idea where the scene is located. Many’s the time I’ve written at the start of a scene or chapter: where is this set? You don’t have to go deep into description (although you can if you want) but give the reader some sense of setting. A few words or a sentence will do: “Oh this is so boring,” she said, setting her book down on the side table and rising from the couch with a yawn.

When the author gives us talking heads.

Closely related to the above point, this is when you have two or more characters talking and it’s all dialogue all the time. Writers who are excellent at writing dialogue can get away with this IF there is an occasional touchdown to the setting. Here you can use location beats: “I’ve had enough,” he said, walking to the kitchen counter. Or you can use on-the-body beats: “I’ve had enough,” he said, running his hands through his hair.

Honestly, taking your writing out of abstraction and into concreteness is simple. It usually takes only a sentence or two, and you’re good to go. But in that simplicity lies enormous improvement in your prose.

Questions? Comments? Where do you run into problems with abstraction in your writing?

My hub and I live in a multi-generational household, a “cottage” behind the home my daughter and her family live in.

Did I give him the rice and tortilla? My lips are sealed.

Written by me.

Written by Claude AI.

Oh!! You’ve really touched something here which resonates for me in the songwriting world. I need those details or else the whole thing becomes musak. And then there’s a whole other phenomenon in songwriting right now where the lyrics are stream-of-consciousness from a badly considered diary and include so many “in” references that they disintegrate into abstraction. Anyhow, you made all of this bubble up in my brain in the wonderful way you do.